THE Antrim coast in the depths of winter is heaven and hell for birds at the same time.

Dúlra loves to take a trip up there at this time of year. You don’t have to go off the beaten track or even wear boots. You can just visit any of the coastal villages here and take a dander along the seafront. You’ll see birds just feet away that twitchers normally only spot through mega-bucks binoculars.

But that rugged coastline seems to have the same effect on birds as a car windscreen has on insects. It’s like they smash off it, or more accurately crash-land on it.

These birds are knackered, desperate, starving. They normally avoid people at all costs. But not in January when they’ve just touched down after travelling across the Irish Sea in a gale. And, just like today’s human refugees, many have fled from lands much further away.

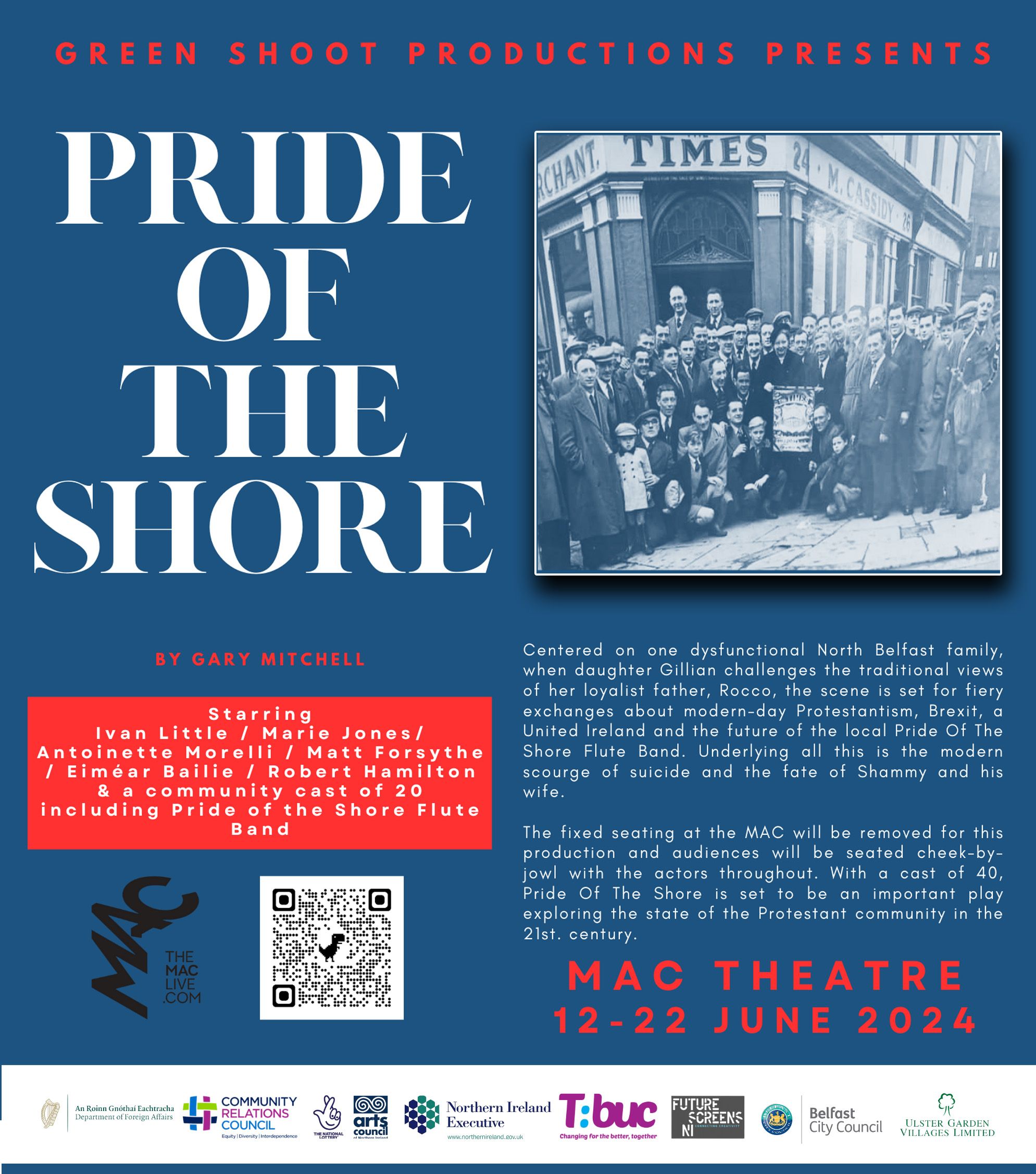

At Whitehead the last remaining twites (gleoiseach sléibhe), a small nondescript finch that breeds among the heather on remote mountaintops, can be found each winter. For some reason a flock always gathers near the boatyard. Twitchers reported them here on the two days before Dúlra’s visit on Monday, but he didn't see any. He’s seen them here before, a dozen birds which are perhaps the last to breed in the whole of the North.

A twite in Whitehead this week

But there were plenty of other birds to be seen. Dúlra looked over the seawall to be greeted by an army of birds of every shape and size on the seaweed below. Many had obviously just arrived and were pecking hungrily, searching for nourishment. It was like the seaweed had come alive – with plovers, pipers, shanks and a multitude of other seabirds.

Dúlra took the path along the seafront to Blackhead Lighthouse, which cuts through the cliffs. Suddenly the sun came out and, for a few moments, something miraculous happened: Millions of flies appeared.

One walker coming in the other direction warned Dúlra with a smile “You’ll need a blowtorch!” And indeed, the flies were so dense that walkers covered their mouths with scarves. The last time Dúlra saw such a swarm was at Lough Neagh – in May!

However, that might not have been the most surprising sight. Dúlra considered calling the coastguard when he passed an angler fishing on a remote rock as giant waves splashed at his feet. This guy must have been as hungry as all those birds!

• Mullaghglass Wetlands Project on the outskirts of West Belfast picked up a deserve Aisling Award – and no wonder, because they’re streets ahead of the rest of the country.

One of the central planks of that group’s bid to coax nature back on to the Belfast Hills is to keep people out. Yes – that’s you and me! It might be hard to accept, but nature in Ireland is at the abyss because we drove it there. You can even include birdwatchers in that group – the reason Lough Neagh barn owl supremo Ciarán Walsh keeps nests secret isn’t because he’s afraid the public will disturb them, but because twitchers will inevitably want to go up and watch this beautiful and rare raptor – and thus scare them away.

The Mullaghglass Wetlands aren’t open to the public and because of that, a whole plethora of rare creatures feel secure enough to come out of hiding.

Now an Oireachtas committee has recommended making some areas of national parks inaccessible to the public so nature can flourish. A great idea, but let’s remember Belfast got there first.

That Oireachtas move was a response to the brilliant Citizens’ Assembly on Biodiversity Loss, which reported last April. That group of 100 people recognised the alarming state of Irish nature and laid out a clear pathway to repairing it.

Chairperson Dr Aoibhinn Ní Shúilleabháín spoke of “an invisible tragedy happening both on land and under water” which involved mass extinction of birds and animals. She said we should “start treating our bogs like our Book of Kells, value our rivers and coastal waters as much as our multinationals, and cherish our forests as a part of our living history”.

But even as we speak, the situation is deteriorating. The report describes the once-famous Irish hedgerow as the “blood supply system of the countryside”, but they are still being lost. In the past couple of years, many miles of hedgerows on the outskirts of West Belfast have been obliterated.

The report says a new national strategy for the protection, maintenance, restoration and expansion of Ireland’s network of hedgerows must be developed urgently and island-wide. It can't happen soon enough.

They point out that by protecting nature we protect ourselves. It’s a message that is in our DNA, our native language and culture hold an intrinsic link with, and inherent respect for, nature and the world around us.

The Oireachtas committee recommends enshrining the rights of nature in the constitution in a referendum. That’s one vote that should get 100 per cent support.

• If you’ve seen or photographed anything interesting, or have any nature questions, you can text Dúlra on 07801 414804.